Here at Ash Tree Books, we are an online bookshop. So the reality is, we are just as much “here” as we are “anywhere”! Presently we do not have a physical storefront, although that is a future dream for us.

For our weekly Collector Blog article, we wanted to share with you the Epilogue from a book by Jorge Carrión, called Bookshops. The title of the Epilogue is called Virtual Bookshops, and that is the reading we share with you below.

Just before we begin we want to introduce the Author, Jorge Carrión. For more than twenty-years, Carrión has visited and explored bookshops across five continents, taking notes, chatting with booksellers, and reading the many books he gathered along the way. This chapter we are about to share with you today is from his book, “Bookshops“.

Virtual Bookshops, by Jorge Carrión

The Epilogue Chapter in his book entitled, Bookshops, A Reader’s History

Over the first few months of 2013, I watched how a bookshop that was almost a hundred years old became a McDonald’s. Of course, it is an obvious metaphor, but that doesn’t make it any less shocking. I am quite sure that the Catalonia, the bookshop that opened its doors on the edges of Plaza de Cataluna in 1924, was not the first to be transformed into a fast-food restaurant, but it is the only time I have personally witnessed such a metamorphosis. For three years I walked past the glass door in the morning and sometimes went in to take a look, buy a book, make in inquiry until suddenly the shutters stayed shit and someone stuck up a precarious notice, barely a page long, which read:

After over eighty-eight years of being open and eighty-two years of activity at Ronda San Pere 3. After surviving a civil war, a devastating fire, a property dispute, the Llibreria Catalonia will close its doors for good.

The severe crisis in the book trade has generated a slump in the sales of books over the last four years that has made it impossible for us to continue in these circumstances and conditions.

Nor could we have prolonged this situation, because we wanted to ensure that the business was closed in an orderly way and met all its obligations. If we had continued any longer, the end would have been much worse.

As we make this decision public we would also like to remember all those who have worked throughout the years in the Llibreria Catalonia and the enterprises that depended on it, especially the Selecta publishing house, and also all our customers–some over decades and generations–and our authors, publishers and distributors. Jointly they have allowed the Llibreria Catalonia to make an important contribution to the culture of Catalonia and Barcelona.

Now and in the future, in all the forms that the dissemination of culture will take, there are and will be individuals, associations, collectives and enterprises ensuring the survival of literature and written culture in general. Unfortunately, the Llibreria Catalonia will not be part of that future.

Miquel Colomer, Director, Barcelona, January 6, 2013

Day after day I was witness to the disappearance of books, to empty shelves, to dust, that great enemy of books, books that were no longer there, only ghosts, memories, books that were gradually being forgotten until one Wednesday there were no shelves for them to be on, because the premises were emptied, filled with workers who yanked out the bookcases and the brackets and the place was all noise and drilling, a din that shocked me for weeks, because I had been used to the silence and cleanliness it had emanated for years; when I walked past that same door, I was met with clouds of dust, carts loaded with rubble, with debris, the gradual transformation of the promise of reading, the business of reading into the digestion of proteins and sugar, the fast-food business.

I have nothing against fast food, I like McDonald’s. Indeed, I am interested in McDonald’s: I search one out most of my trips, in order to try the local specialties, because there is always a breakfast or a fajita or a hamburger or a sweet that is the McDonald’s version of one of the favourite dishes of the locals. However, that didn’t make this supplantation any less painful. For months, every morning I watched the destruction of a small world, occupying that same space like an ambassador from another world, and in the afternoons I read about reading and finished writing this book.

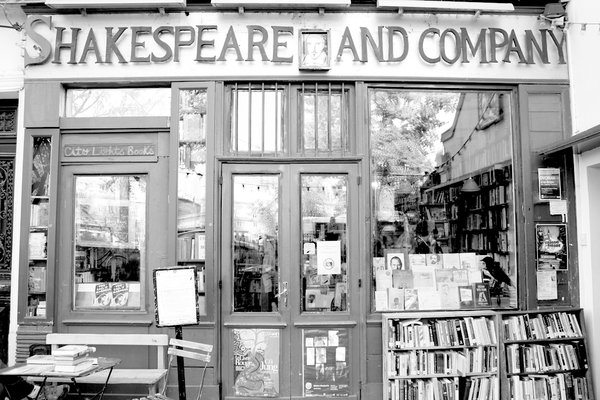

Green Apple Books–as Dave Eggers recalls in his chapter in the anthology My Bookstore–is lodged in a building that has survived two earthquakes that brought turmoil to San Francisco in 1906 and 1989; perhaps that is why one experiences between its shelves the feeling that “if a bookshop is as unorthodox and strange as books are, as writers are, as language is, it will all seem right and good and you will buy things there.” I bought there a short bilingual book, published by a Hong Kong poetry festival, the English title of which is Bookstore in a Dream. Four lines about the bookshop as a quantum fiction really caught my attention: its multiplication through space, its mental realm, its existence in parallel universes on the Internet, a compulsive survivor of all earthquakes. If Danilo Kis narrator dreams of an impossible library that contains the infinite Encyclopedia of the Dead, Lo Chih Cheng dreams of a bookshop that cannot be mapped out. A bookshop, like any other, that is soothingly physical and horribly virtual. Virtual because digital, or mental or because it has ceased to exist. A bookshop that is born, like Lolita in Santiago de Chile, like Bartleby and Company in Berlin or Valencia, like Bartleby and Company in Berlin or Valencia, like Libreria de la Plata in Marginal Sabadell. Like Doria Llibres, which has filled the space left by Robafaves in another small Catalan city, my Mataro: at what point do projects become completely real? Bookshops of the memory, gradually invaded by fiction.

Like the shop run by the wise Catalan in One Hundred Years of Solitude, who came to Macondo during the Banana Company boom, opened his business and began to treat the classics and his customers as if they were members of his own family. Aureliano Buendia’s arrival in that den of knowledge is described by Gabriel Garcia Marquez in terms of an epiphany:

He went to the bookstore of the wise Catalonian and found four rantings boys in a heated argument about the methods used to kill cockroaches in the Middle Ages. The old bookseller knowing about Aureliano’s love for books that had been read only by Venerable Bede, urged him with a certain fatherly malice to get into the discussion, and without even taking a breath, he explained that the cockroach, the oldest winged insect on the face of the earth, had already been victim of slippers in the Old Testament, but that since the species was definitely resistant to any and all methods of extermination, from tomato slices with borax to flour and sugar, and with its one thousand six hundred and three varieties had resisted the most ancient, tenacious, and pitiless persecution that mankind had unleashed against any living thing since the beginning, including man himself, to such an extent that just as an instinct for reproduction was attributed to humankind, so there must have been another one more definite and pressing, which was the instinct to kill cockroaches, and is the latter had succeeded in escaping human ferocity it was because they had taken refuge in the shadows, where they became invulnerable, because of man’s congenital fear of the dark, but on the other hand they became suscepticle to the glow of noon, so that by the Middle Ages already, and in present times, and per omnia secula seculorum, the only effective method for killing cockroaches was the glare of the sun. The encyclopedic coincidence was the beginning of a great friendship. Aureliano continued getting together in the afternoons with the four arguers, whose names were Alvaro, Gernan, Alfonso and Gabriel, the first and last friends that he ever had in his life. For a man like him, holed up in written reality, those stormy sessions that began in the bookstore at 6:00 p.m. and ended at dawn in the brothels were a revelation.

That wise Catalan was in fact Ramon Vinyes, the Barranquilla bookseller, cultural activist, and founder of Voces magazine (1917-20), first Spanish immigrant, then Spaniard in exile, teacher, dramatist and storyteller. His bookshop, R. Vinas & Co, a pre-eminent cultural centre, was burnt down in 1923 and is still remembered today in Barranquilla as one of the mythical bookshops of the Columbian Caribbean. When he went into exile in Latin /America as a Republican intellectual after crossing France, he took up teaching and journalism and became the master of a whole young generation known as “the Barranquilla Group” (Alfonso Fuenmayor, Alvaro Cepeda Samudio, German Vargas , Alejandro Obregon, Orlando Rivera “FIgurita,” Julio Mario Santo Domingo, and Garcia Marquez). On one of my strangest mornings ever, I gave the taxi driver at the Barranquilla bus station the following address: calle San Blas, between Progreso and 20 de Julio. Libreria Mundo. As we drove on, he told me that the names had changed, he did some consulting and discovered that I was referring to calle 35 between Carrera 41 and 43. We headed there. The Libreria Mundo run by Jorge Rondon Hederich was where the legendary group of intellectuals met, the spiritual heir of R, Vinas & Co. that had been reduced to ashes twenty years earlier. When I got there, I discovered that it too, no longer existed. It was obvious, but neither Juan Gabriel Vasquez (who had given me the information) nor I had thought to check it. The bookshop should have been there, but it wasn’t, because for quite some time it had only existed in books:

In any case, the axis of our lives was the Libreria Mundo at twelve noon and six in the evening, on the busiest block of calle San Blas. German Vargas, an intimate friend of the owner, Don Jorge Rondon, was the one who convinced him to open the store that soon became the meeting place for journalists, young writers and politicians. Rondon lacked business experience, but he soon learned, and with enthusiasm and a generosity that turned him into an unforgettable Maecenas. German, Alvaro and Alfonso were his advisers in ordering books, above all the new books coming from Buenos Aires where publishers had begun the translation, publication and mass distribution of the new literature from all over the world following the Second World War. Thanks to them we could all read in a timely way books that otherwise would not have come to the city. The publishers themselves encouraged their patrons and made it possible for Barranquilla to again become the centre of reading it had been years earlier until Don Ramon’s historic bookshop ceased to exist. It was not long after my arrival when I joined the brotherhood that waited for the travelling salesman from the Argentinian publishers as of they were envoys from heaven. Thanks to them we were early admirers of Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortazar, Felisberto Hernandez, and the English and North American novelists who were well translated by Victoria Ocampo’s crew. Arturo Barea’s Making of Rebel was the first hopeful message from a remote Spain silenced by two wars.

That is Garcia Marquez writing about those two bookshops, the one he didn’t know and the one he visited, both melded into one in the virtual reality of his masterpiece. I have been unable to find photographs of R. Vinyes & Co. or on the web and now I realize that his books has found its rhythm in searches inside material books and on the non-material screen, a syntax if to-ing and fro-ing as continuous and discontinuous as life itself; how Montaigne would enjoy the ability of search engines to generate associations, links fertile byways and analogies. How his heir, Alfonso Reyes, would also have learned from them about whom the narrator of the first part of The Savage Detectives says: “Reyes could be my little home. Reading only him and those he liked one could be incredibly happy.” In books and bookshops in Antiquity the erudite Mexican noted:

Parchment was cheaper and more resistant than papyrus, but the book trade did not adopt it as a matter of course[…]Ancient producers of books preferred this light, elegant material, and there was a degree of aversion towards the weight and coarseness of parchment. Galen, the greatest doctor from the second century AD, was of the opinion that, for reasons of hygiene, shiny parchment hurt and tired eyes more than smooth opaque papyrus that did not reflect the light. Ulpioanus the jurist (died AD 229) examined as a legal problem the issue of whether codices made of vellum or parchment should be considered as books in library bequests, something that did not even have to be debated in the case of papyrus items.

Almost two millennia later, the slow transition from reading paper to reading onscreen gives these arguments a contemporary twist. We now wonder of the screen and the light it radiates do more damage to the eyes than electronic ink, which does not allow us to read in the dark. Or whether, after someone’s death, it is right for heirs to inherit, through books, vinyl records, CD’s and hard discs, the songs and texts their parents bought for themselves. Or whether television and video games harm the imagination of children or adolescents, because they simulate their reflexes but damage the activity of their brains and are so violent. As Roger Chartier has studied in Inscription and Erasure, Written Culture and Literature from the Eleventh to the Eighteenth Century, it is the Golden Age Castile that the danger fiction represents for the reader is first formally expressed, with Don Quixote arousing the greatest social fear: “In the eighteenth century, the discourse is medicalized and constructs a pathology of excessive reading that is thought to be an individual sickness or collective epidemic.” In this period the reader’s sickness is related both to the arousal of the imagination and the immobilizing of the body: the threat is as mental as it is physiological. Following this thread, Chartier analyses the eighteenth -century debate over traditional reading that was called intensive, and modern reading that was said to be extensive:

According to this dichotomy, suggested by Rolf Engelsing, the intensive reader was confronted by a restricted range of texts that were read and reread, memorized and recited, listened to and learnt by heart, transmitted from generation to generation. Such a way of reading was heavily impregnated with sacred purpose, and subjected the reader to the authority of the text. The extensive reader, who appears in the second half of the eighteenth century, is very different and reads countless new, ephemeral printed works and devours them eagerly and quickly. His glance is distanced and critical. In this way, a communitarian, respectful relationship is replaced by irreverent, self-assured reading.

Our way of reading, inextricably linked to screens and keyboards, must be about the spread, books having been at an ever-increasing rate, of more and more audio-visual information and knowledge platforms, of that broadening out, with all its political implications. The loss of the ability to concentrate on a single text brings the gain of a glimmer of light, critical, ironic distance, the ability to relate and interpret simultaneous phenomena. Consequently, it brings an emancipation from authorities that restrict the range of reading, the deconsecration of an activity that by this stage in evolution should be almost natural: reading is like walking, like breathing, something we do without even having to think.

Whilst the apocalyptically minded revamped worn-out arguments from worlds that no longer existed rather than accepting perpetual change as the immutable engine of History, Fnac bookshops filled up on video games and television series and prestigious bookshops began to sell commentaries about video games and television series, as well as eReaders and eBooks. Because the moment a style ceases to be a fashion or trend and becomes mainstream, it will probably undergo a process of sophistication and end up on bookshop and library shelves and in museum rooms. As a cultural product. As a work of art. As a commodity. Scorn of emerging and mainstream styles is fairly common in the world of culture, a field–as the all are–dominated by fashion, the ego and the economy. Most of the bookshops I have mentioned in this essay, on the international circuit where I have slotted myself in as tourist and traveller, nurture a class fiction to which greater millions now have access–fortunately–but they are still a minority. We represent the broadening out of the chosen people that Goethe met in the Italian bookshop. A class of fiction that is eminently economic–as they all are–even though it wears a veneer of an education that is more or less refined. We should not deceive ourselves: bookshops are cultural centres, myths, spaces for conversations and debate, friendships and even amorous encounters, due in part to their pseudo-romantic paraphernalia, which is often championed by readers who love their craftsmanship, and even by intellectuals, publishers and writers who know they form part of culture. But above all bookshops are businesses. And their owners, often charismatic booksellers, are also bosses, responsible for paying the wages of their employees and ensuring their labour rights are respected, managers, overseers, negotiators skilled in the ins and outs of labour legislation. One of the most inspiring and sincere pieces of those gathered together in Rue de l’Odeon is in fact the one that links freedom to the purchase of a book:

For us the business has a deep and very moving meaning. In our view a shop is a real magic chamber: when a passer-by crosses the threshold of a door that anyone can open, enters this this impersonal place, one might say that nothing changes the expression on his face or his tone of voice: with a feeling of total freedom he is carrying out an act he believes has no unexpected consequences.

But which in fact is defined by those consequences: James Boswell will meet Samuel Johnson in Ton Davies’ bookshop on Russell Street; Joyce will find a publisher for Ulysses; Ferlinghetti will decide to open his own bookshop in San Francisco; Josep Pla will enter the Canet bookshop in Figueras as a child and seal his pact with literature; William Faulkner will work in one as a bookseller; Vargas Llosa will buy Madame Bovary in a bookshop in the Quartier Latin in Paris a long time after seeing the film in Lima; Jane Bowles will meet her best friend in Tangier; Jorge Camacho will buy Singing from the Well in a bookshop in Havana and become Reinaldo Arenas’ main champion in France; a psychiatrist will advise a juvenile delinquent by the name of Liminov to go to bookshop 41 in a provincial Russian city and this will make a writer of him; Francois Truffaut will find a novel by Henri-Pierre Roche entitled Jules and Jim among second-hand books in Delamaine in Paris; one night in 1976 Bolano will read the “First Infra-realist Manifesto” in Ghandi Bookshop in Mexico City; Cortazar will discover Cocteau’s work; Vila-Matas will find Borges. Perhaps it was only once that the fact somebody did not enter a bookshop had positive outcomes: one day in 1923, Akira Kurosawa headed off to Tokyo’s famous Maruzen bookshop, renowned because of its building constructed by Riki Sano in 1909 and for importing international titles for the Japanese cultural elite. He was planning to buy a book for his sister, but he found that the shop was shut and left; two hours later, an earthquake destroyed the building and the whole district was consumed by flames. Literature is magic and exchange, and for centuries has been sustained, like money, by paper, which is why it has fallen victim to so many fires. Bookshops are businesses in two simultaneous, inseparable levels: the economic and the symbolic, the sale of copies and the creation and destruction of reputations, the reaffirmation of dominant taste or the invention of a new one, stocks and credits. Bookshops have always been the canon’s witches’ Sabbath and hence key points in cultural geopolitics. The place where culture becomes more physical and thus more open to manipulation. The spaces where, from district to district, town to town, city to city, it is decided what reading matter people will have access to, what is going to be distributed and thus open to the possibility of being consumed, thrown away, recycled, copied, plagiarized, parodied, admired, adapted or translated, It is where their degree of influence is mainly decided. It was not for nothing that the first title Diderot gave to his Letter on the Book Trade was: “A political and historical letter written to a magistrate about the Bookshop, its present and ancient status, its rules, its privileges, its tacit limits, the censors, itinerant sellers, the crossing of bridges and other matters related to the control of literature”.

The Internet is changing that democracy–or dictatorship, depending on how you look at it–of distribution and selection. I often buy titles published in cities I have visited and was unable to buy when I was there from Amazon or other web stores. Last year, on my return from Mexico City, where I exhausted a dozen bookshops looking for an essay by Llished by Luis Felipe Fabre published by a small Mexican publishing house, I decided to look on the Casa del Libro page and there it was and cheaper than in its place of origin. If Google is the Search Engine and Barnes & Noble the Book Chain, it hardly needs to be said that Amazon is the supreme Virtual Bookshop. Though that is not very precise: even if it was born in 1994 as a bookshop with the name of Cadabra.com and soon after switched to Amazon in order to shoot up the alphabetical pecking order that ruled the Internet before Google, the truth is that for some time it has been a big department store where books are as important as cameras, toys, shoes, computers or bicycles, although the brand bases its power to pull in customers on emblematic devices like Kindle, a reader or electronic book that creates customer loyalty. Indeed, in 1997 Barnes & Noble took it to court over its deceitful advertising (that tautology): the slogan “The world’s greatest bookstore” was not true because Amazon was a book broker and not a bookstore. Now it deals in anything that is on offer, except for eReaders that are not Kindles.

We are innate searchers of the physical world–my hunt for the non-existent bookshop in Barranquilla is only one example from a thousand–and cannot stop being that in a virtual world as well: the history of the electronic book is as gripping as a thriller. It began in the 1940s, gathered speed in the 1960s with hypertext publishing and found a format in the 1970s thanks to Michael S. Hart and a description (“electronic book”) thanks to Professor Andries Van Damme, of Brown University, in the middle of the 1980s. When Sony launched its book reader in 1992 with the Data Discman CD, it did so with the tag “The library of the future.” Kim Blagg got the ISBN for an electronic book in 1998. These are the data, the possible chronologies, the clues that, when combined, create the feeling that we are caught between two worlds, as were Cervantes’ contemporaries in the seventeenth century, Stefan Zweig’s at the beginning of the twentieth or the inhabitants of Eastern Europe the end of the 1980s. In a slow apocalypse in which bookshops are at once oracles and privileged observatories, battlefields and twilight horizons in an irrevocable process of mutation. As Alessandro Baricco says in The Barbarians:

It is a mutation. Something that concerns everyone, without exception. Even the engineers, up there on the wall’s turrets are already starting to take on the physical features of the very nomads they, in theory, are fighting against and they have nomadic coins in their pockets, as well as dust from the steppes on their starched collars. It’s a mutation. Not some minor change or inexplicable degeneration, or mysterious disease, but a mutation undergone for the sake of survival. The collective choice of a different, salutary habitat. Do we have even the vaguest sense of what could have generated it? I can certainly think of a number of decisive technological innovations, the ones that have compressed space and time, squeezing the world. But these probably would not have been enough had they not coincided with an event that threw open the whole social scene: the collapse of the barriers that until now had kept a good part of humanity far from the routines of desire and consumption.

The word desire reappears yet again in this book, that chemical energy that draws us to certain bodies and objects, vehicles towards manifold knowledge. In the post-1991 world, with neo-liberalism strengthened by the fall of the Soviet Union, and increasingly digital and digitized, that desire has been assuming material form in the consumption of the pixel, that smallest unit of information with which we make sense of our writing, photographs, conversations, videos and maps that explain the routes where we sweat, drive, fly or read. That is why bookshops have web pages: in order to sell us pixelated books, and so we also consume images, stories, the latest novelties and gimmicks. All this is substantial, not mere accident: our brains are changing, the way we communicate and relate is changing: we are the same but very different. As Baricco explains, in recent decades, what we understand by experience and even the tissue of our existence has changed. The consequences of this mutation are as follows: “Surface rather than depth, speed rather than reflection, sequences rather than analysis, surfing rather than penetration, communication rather than expression, multitasking rather than specialization, pleasure rather than effort.”

An exhaustive dismantling of the machinery of nineteenth-century bourgeois thought, a final destruction of the last debris of the shipwreck of the divine in everyday life. The political victory of irony over the sacred. It is much more difficult for the few gods of old that survived two worlds on paper to continue to harass us from the dull glow of the screen.

Cultures cannot exist without memory, but need forgetfulness too. While the Library insists on remembering everything, the Bookshop selects, discards, adapts to the present thanks to a necessary forgetfulness. The future is built on obsolescence; we have to discard past beliefs that are false or have become obsolete, fictions and discourses that do not shed the faintest light. As Peter Burke has written: “Discarding knowledge in this way may be desirable or even necessary, at least to an extent, but we should not forget the losses as well as the gains.” That is why once the inevitable process of selecting and discarding has taken place, one should “study what has been dispensed with over the centuries, the intellectual refuse,” where humanity might have got it wrong, where what was most valuable might have been cast into oblivion, among data and beliefs that did deserve to disappear. After so many centuries of long-term survival, books due to electronic sourcing, are entering into the logic of inbuilt obsolescence, of a sell-by date. This will bring an even more profound change to our relationship with texts we are going to be able to translate, alter and personalize to an unimaginable degree. It is the crossroads on the journey that began with humanism when philology questioned useless, hackneyed authorities and Bibles began to be turned into our languages via rational criteria and not according to the say-so of superstition.

If there are still many of us who keep collecting futile stamps on our foolish passports to the bookshops of the world it is because we find there the remains of cultural gods that have replaced the religious sort. From Romantic times to present, like archaeological ruins, like some cafes and so many libraries, or cinemas and museums of contemporary art, bookshops have been and still are ritual spaces, often marked out by tourism and other institutions as ways to understand the history of culture, erotic topographies, and stimulating contexts to find material to nourish our place in the world. If with the death of Jakob Mendel or the hypertext of Borges those physical places we can cling to become more fragile and less transcendent, with the Internet they are much more virtual than our imagination might suggest. They compel us to create new mental tools, to read more critically and more politically than ever, to imagine and connect as never before, analyzing and surfing, going deeper and more rapidly, transforming the privilege of unheard-of access to Information into new forms of Knowledge.

I devote many of my Sunday afternoons to surfing the web in search of bookshops that still do not exist, though they are out there waiting for me. For years, I have been a reader-viewer of emblematic places I have yet to visit. Very recently, chance enabled me to get to know two of them: in Coral Gables, whose name had always evoked Juan Ramon Jimenez, twenty-four hours of unexpected stopover allowed me to go to Books & Books, a beautiful Miami bookshop housed in a Mediterranean-style building from the 1920s. One weekend in Buenos Aires when I had nothing planned, I decided to take the ferry and visit Montevideo to finally discover in person an even more beautiful, equally well-stocked bookshop, Mas Puro Verso, with its art deco architecture from the same era and glass display cabinet at the top of its imperial stairs. Just as I coveted those spaces, I have spent years collecting leads to others in books, magazines, web pages or videos. For instance, Tropismes in a nineteenth-century arcade in Brussels; Les Bals des Ardens in Lyons with that grand door made from books and Oriental carpets that invite one to read on the floor; Bordeaux’s Mollat, which has just turned every booklover’s dream into a reality: the chance to spend a night in a bookshop, and whose website is always bubbling with ideas and activities, a wholly family tradition transformed into 2,500 metres of printed culture overflowing from the very same house where no less a figure than the traveller-philosopher Montesquieu lived, wrote and read at the beginning of the eighteenth century; Candide, its architecture as light as a bamboo, in Bangkok, run by the writer, publisher and activist Duangruethai Esanasatang; Athenaeum Boakhandel in Amsterdam, which Cees Nooteboom empathetically recommended to me for its classical aesthetics and above all, for its importance as a cultural centre and writers’ residence; Pendleburys. a country house devoured by a Welsh forest; Swipe Design in Toronto, because an antique bicycle hangs from its ceiling and a chessboard sits between its two readers’ armchairs; Ram Advani Booksellers, the mythical shop in Lucknow, although now I will not be able to meet Ram Advani, who died at the end of 2015 at the age of ninety-four, and whose memory is perpetuated by his daughter-in-law, Anuradha Roy; and Atomic Books, the favourite bookshop of Santiago Garcia the scriptwriter and comics critic who in an email told me that it is one of the best in the US for a reader of graphic novels, though they also sell literature, countercultural fanzines and even toys and punk records: “What’s more, you can meet John Waters picking up his mail.” I have no information about the history or importance of others, photographs have simply captivated me, because everything I have about them is in languages like Japanese, which I do not understand: Orion Papyrus, in Tokyo, with its parquet floors, its lights worthy of Mondrian and that blend of wood and metal in shelves full of art and design books, or Shibuya Publishing & Booksellers in the same city, with bookshelves on every imaginable geometric shape.

And if I ever return to Guatemala City, I will fight against my nostalgia for El Pensativo, which has disappeared, and will religiously repair to Sophos. I expect I will jot down notes on them all when I pay them a visit, like someone who is paying off their debts, in a notebook similar to the one I used on my far-off trip, because I have given up on my iPad’s Moleskine app and do not like my mobile phone doubling as a camera and a notebook. You see: what matters, in the end, is the will to remember.

In “Convert Joy”, a story by Clarice Lispector, we meet a girl who was “fat, short, freckled and had reddish, excessively frizzy hair” but who had “what any child devourer of stories would wish for: a father who owned a bookshop.” Many years ago I started to peel off the sticker with the price and barcode on any book I bought and stick them on the inside of the back cover next to the anti-theft chip. It was my way of maintaining an almost fatherly link. The last wish of writer David Makson, who died in New York in June 2012, was for his library to be sold in its entirety to the Strand and thus be scattered among all those many, many libraries of innumerable anonymous readers. For one dollar, or twenty, or fifty, his books went there, were reintegrated into the market where they once belonged to await thier fate and fortune. Markson could have bequeathed his library to a university, where it would have accumulated dust and been visited by the few specializing in his work, but he opted for the opposite move: to share it around, break it up and subject the risk of totally unexpected future readings. When the news broke, dozens of the followers of the author of This is Not a Novel rushed to Manhatten bookshop to locate his annotated, underlined books. A virtual group was set up. Scanned the pages started to be published on the Internet. In his copy of Bartleby the Scrivener, Markson underlined every appearance of the phrase “I would prefer not to go”; in White Noise, he alternated “astonishing, astonishing, astonishing” with “boring, boring, boring”; in a biography of Pasternak he wrote in the margin: “It is a fact that Isaak Babel was executed in the basement of a Moscow prison. A very strong possibility that the manuscript of an unpublished novel is still around in Stalin’s archives.” Once could turn all the marginal comments in Markson’s library into one of his fragmentary novels, where notes on reading, poetic impressions and reflections follow on as if it were a zapping session. It would be an impossible novel because nobody is ever going to find all the books that made up his library: many of them were bought or are being bought by people who do not know who Markson was. That gesture forms part of his legacy. A final, definitive gesture combining death, inheritance, paternity and a single one of the infinite bookshops that sum up all the rest, a unique story dedicated to world literature.

Ideas only exist in things.

David Markson, The Loneliness of the Reader

Here is an image of the book we just shared this chapter from. If you click on the image it will take you to Amazon where you can purchase the book.

Jorge Carrión, the Author of the book entitled “Bookshops”

Jorge Carrión, the Author of the book entitled “Bookshops”

At Ash Tree Books, I am quite amused at the irony of supporting the author in this manner but we are nonetheless happy to direct you to the sale of his entire book as it is quite a thought-provoking vivid entertaining meditation on bookshops past, present and future. In it, Carrión explores the importance of the bookshop as a social, cultural and intellectual space. Although we are still just a Virtual Bookshop, we hope to provide a type of positive experience for all our visitors, and one day, if we continue to dream about it, maybe Ash Tree Books can become a “real” bookshop!

We hope you enjoyed this read!