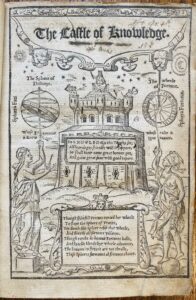

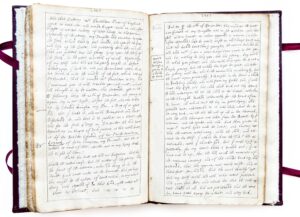

Machynlleth’s professional Tolkien collector has shared his tips and tricks ahead of the new Lord of the Rings movie release. This article was published in Cambrian News by Debbie Luxon Mark Faith has been collecting rare editions of Tolkien books since 2003, hosting a…