It’s hidden deep within a city museum and prized worldwide – but we’re betting you’ve never even heard of it, let alone seen it.

This article was published in Glasglow Live by Craig Williams.

Glasgow is home to an incredible number of remarkable treasures, many of which can be found within the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow, forming part of William Hunter’s original collection that he assembled to ‘improve knowledge of the world’.

Thanks to the anatomist and physician, who was an avid collector of coins, medals, paintings, shells, minerals, books and manuscripts, we have Scotland’s oldest museum and one of its most important cultural assets right here on our doorstep in the University of Glasgow.

And a visit to the wonderful museum allows us to marvel at items like ethnographic objects from Captain Cook’s Pacific voyages, the incredible map of the world prepared for Chinese Emperor Kangxi in 1674 by Jesuit missionary Ferdinand Verbiest, and a bronze drachma coin of Egyptian queen and ruler Cleopatra VII – the best example in the world of a Cleopatra coin.

But housed deep within the Hunterian Library – a rare book collection that contains around 10,000 printed books and 650 manuscripts – lies an object few Glaswegians will have ever heard of. It could well be regarded as the city’s greatest and most unusual treasure and one which lay ‘undiscovered’ or ‘lost’ for over 200 years –the Historia de Tlaxcala.

The Historia de Tlaxcala, also known as the Codex Tlaxcala, is a 16th century illustrated manuscript originating in post-Spanish conquest Mexico that deals with the social, political, military, religious and cultural history of the Province of Tlaxcala (which means ‘the place where tortillas are made’) and the Tlaxcalan people.

It was written by mestizo (of a white European and indigenous background) historian and landowner Diego Muñoz Camargo, the son of Juana de Navarra, a noblewoman from Tlaxcala and the Spanish conquistador Diego Muñoz Camargo, who accompanied Hernán Cortés on the expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and claimed Mexico for Spain.

The Historia is regarded as highly unusual, and historically important as it can be separated into three different sections, one textual and two pictorial. It is written in Spanish and native Náhuatl – the language spoken by the Aztecs from which words like avocado (ahuacatl), chocolate (xocolātl), guacamole (ahuacamolli) and tomato (tomatl) owe their origin too.

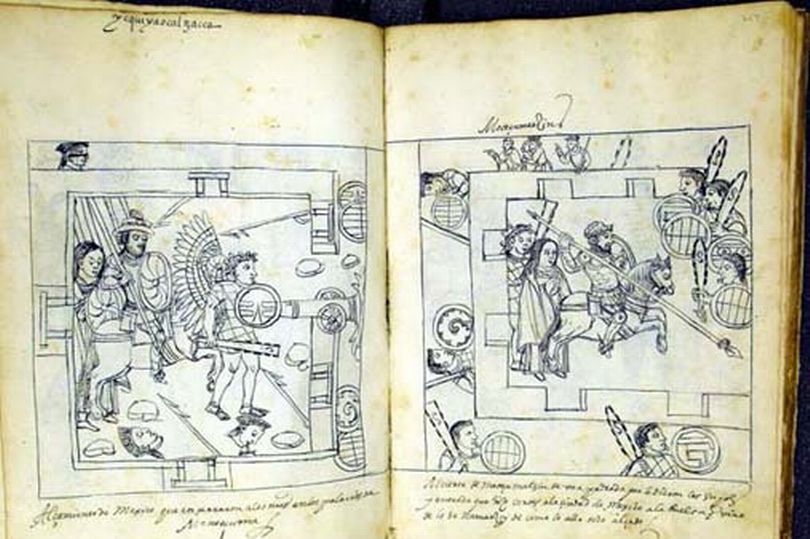

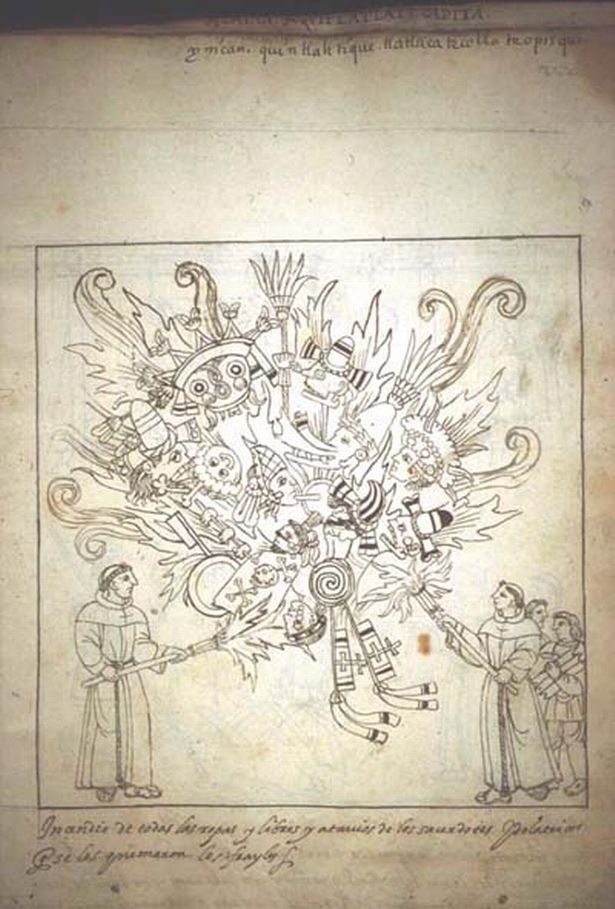

Written on European paper, the manuscript survives still bound in its original vellum with gilded and goffered edges. It comprises 318 folios, 234 of which correspond to Camargo’s Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala text, with folios 236 to 317 corresponding to a series of 156 drawn images in pen and china-ink that are captioned above in Náhuatl, with each image and caption glossed underneath in Spanish by a different hand.

Around eighty of the drawings appear to be nearly identical to those found on the Lienzo de Tlaxcala – a now lost mid-16th century Mexican manuscript painted on a sizeable piece of linen or amatl (native paper sheet) by tlaxcalan leaders and which may have acted as a form of template for the Codex – one possibly produced based on lithographs from tracings of the original.

500 years ago the people of Tlaxcala (Mexico’s smallest state) made a strategic alliance with the Spanish conquistadors and joined with them to capture Tenochtitlan, the seat of the Aztec empire that later became Mexico City, in 1521 in what was a decisive event in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire that changed world history.

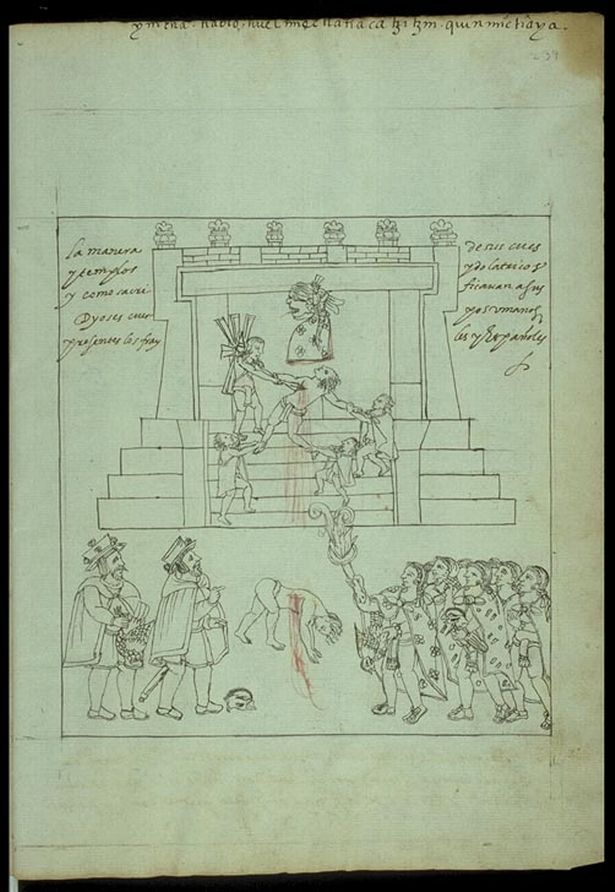

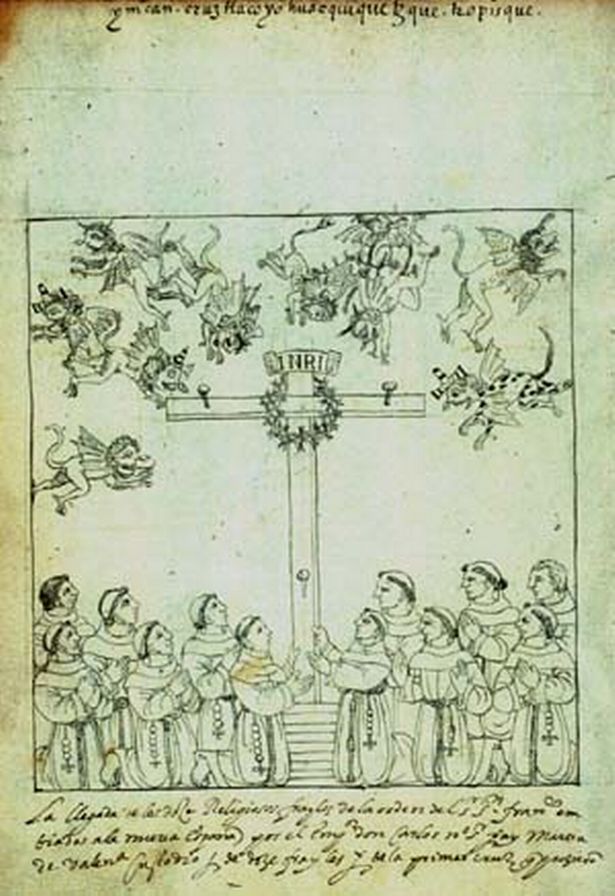

The codex deals with the joint history of the Tlaxcaltecas and the Spanish in their wars against the Aztecs and the evangelical battle for Christianity, and charts the history of the province from the beginning of the region’s conquest by the conquistadors.

It depicts scenes such as a human sacrifice ceremony, the death of the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II, the erection of the first cross in New Spain and Christopher Columbus symbolically offering the “New World” to King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

One of the most impressive elements of the codex – and what it makes it so historically important – is that it potentially uncovers the truth as to how Moctezuma II died during the Fall of Tenochtitlan.

To this day debate and controversy surrounds his death, with traditional Spanish accounts, including first-person narrative The Conquest of New Spain by conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo (which everyone should read), attributing his death to wounds he received from being hit by stones and spears thrown from his subjects onto the roof of his palace, which Hernán Cortés had hauled him onto to plead with them to stop attacking the Spanish.

However, the codex depicts Moctezuma on the roof calling for calm from his subjects and ordering their retreat as two Spaniards approach from behind, one holding a chain threateningly in his hand – suggesting he was strangled to death by the Spanish there on the roof in full view of his people below.

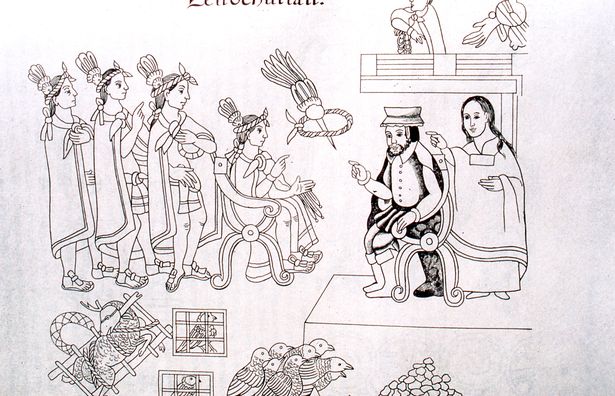

nterestingly, the codex also depicts the historic first ever meeting which took place outside the city of Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, between Moctezuma II and Hernán Cortés, alongside his interpreter and companion La Malinche (or Malintzin), one of 20 enslaved indigenous women given to the Spaniards who would go on to play a hugely important role in the conquest and who gave birth to Cortés’s first son, considered one of the first mestizos in history.

Unlike another 16th century codex written by Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún called the Florentine Codex, La Malinche is depicted in the Codex Tlaxcala wearing her hair loose and hanging down her shoulders, which experts such as Dr Claudia Rogers, in her article Malintzin as a Conquistadora and Warrior Woman in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, believes helps to challenge notions that, rather than act as a ‘peaceful mediator’, she was seen “as a powerful warrior or conquistadora, who was intricately connected with violent acts of conquest”.

As a side note, La Malinche remains such an incredibly potent figure within Mexican life even 500 years on that the term ‘malinchismo’ is used to refer (negatively) to people (or ‘traitors’ even) who feel an attraction to foreign cultures and disregard for their own culture – i.e. folk that prefer drinking Coca-Cola to Jarritos or eating McDonald’s to Mexico City’s famous tacos al pastor.

Written between 1580 and 1585, the manuscript made its way in 1585 from Mexico to Spanish King Felipe II’s Royal Library of the San Lorenzo de El Escorial near Madrid.

It appears to have remained there until at least the early 17th century after which its fate becomes obscure, until the early eighteenth century when William Hunter was – through reasons unknown – able to purchase the manuscript in 1768.

In an article entitled Los Mejicanos en El Salvador, cultural anthropologist Marvin Aguilar goes as far to suggest that, rather than end up in Madrid, “It can be deduced, due to its inexplicable appearance in the possession of the Scottish doctor William Hunter that the manuscript was stolen by English pirates during its transfer from Mexico to Spain”.

What we do know is that, following Hunter’s death in 1783, it passed to the ownership of Glasgow University after he bequeathed his vast collection of items to the institution.

Known throughout the Spanish-speaking world as the ‘Manuscrito de Glasgow’, it is said to have remained largely unknown to Aztec experts for hundreds of years – as evidenced by the fact that it was absent from a census on Mesomaerican manuscripts conducted in 1975.

However, that changed six years later when Mexican scholarRené Acuña published the first facsimile edition of the manuscript under the title Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala, Mexico in 1981, some 213 years after it was purchased somehow by William Hunter to add to his collection back in 1768.

This led to the Historia gaining “deserved and widespread recognition as one of the most historically important early Mesoamerican documents extant”, and has since led to it being exhibited all over the globe, including in Mexico at the Museo de la Memoria de Tlaxcala of all places, as well as the Royal Academy’s Aztecs exhibition in London back in 2002/2003 – which at the time was the most comprehensive survey of Aztec culture ever mounted, and was also central to the British Museum’s exhibition, Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler, which ran from 2009 to 2010.

A recognition that perhaps should also extent to Glasgow, especially since the Spanish-speaking world use the name of the city when referring to the unique treasure to be found in the a library collection of a city that has yet to really appreciate the fact that it is, somehow, home to one of the most historically important Aztec treasures ever written.

You can check out the direct link to this article on the Glasglow Live website here:

https://www.glasgowlive.co.uk/news/glasgow-news/lost-aztec-manuscript-lay-glasgow-20829782

Exactly!